Charles Fuller’s “A Soldier’s Play” was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1982. Loosely based on Herman Melville’s “Billy Budd,” it was originally staged by the off-Broadway Negro Ensemble Company and made into a widely praised 1984 film (as “A Soldier’s Story”), with several holdovers from the play, including Adolph Caesar, who won the Supporting Actor Oscar for his challenging role, and Denzel Washington in a pivotal one. The current Roundabout Theatre Company revival is the first Broadway production. (Revivals in 1996 and 2005 were off-Broadway.)

There is story and there is plot, as Stephen Sondheim said recently about “West Side Story,” and a good play combines the two. “A Soldier’s Play” is a good play, whose story is simple: A U.S. Army Sergeant has been shot to death on a stateside base by a person or persons unknown and a commissioned Captain has been assigned to solve the mystery.

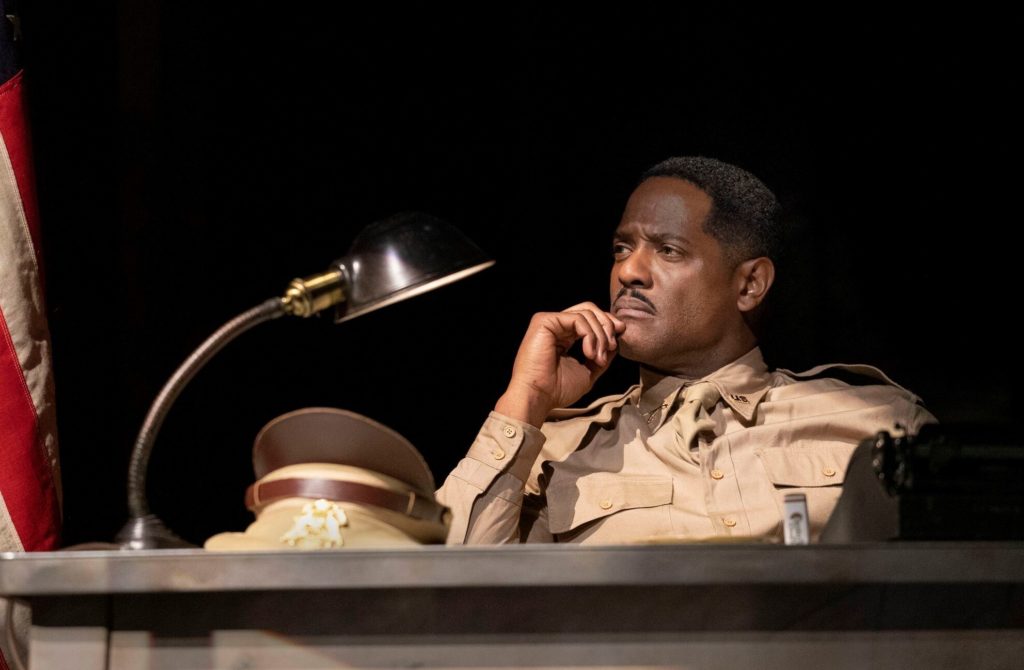

Then there’s the plot, which thickens with added factors: it is 1943 at racially segregated Fort Neal in Louisiana during WW II, and the victim, Sgt. Vernon C. Waters, played by David Alan Grier (who appeared in a smaller role in the movie), is black. Wanting to keep the case low-profile (and to cover their white asses), military higher-ups assign African-American Captain Richard Davenport (Blair Underwood) to the case.

Rare enough at his Washington, D. C. home base, Davenport is the first black officer anyone at Fort Neal has ever even seen, no less reported to. As such, he faces resistance from the white Commanding Officer, Captain Charles Taylor (Jerry O’Connell), and near-reverent awe from the enlisted men of Sgt. Waters’ all-black unit. The result is a solid whodunnit plus a probing examination of racism, especially within the black ranks themselves.Possible suspects include members of the sergeant’s own company, a white officer, and rednecks from the nearby town. The investigation (story) probes the characters of the men involved (plot). (A seemingly minor point about the killing, brought to Davenport’s attention by an enlisted man, provides a gruesome glimpse into possible motivations of KKK assassins.) The play unfolds like a courtroom drama with interior and exterior sidebars and flashbacks, sharply isolated by Alan Lee Hughes’s lighting, and when Davenport addresses the audience, they, consciously or not, take on the collective feel of a jury.

The seven enlisted soldiers (of the twelve-men cast), while distinct individuals, are indeed a unit, protective of one another and itching to get into the WW II action. And they present as real soldiers. Except for the absence of cursing – the play pre-dates the on-stage F-bomb era – the barracks atmosphere and relationships feel authentic, down to such details as saluting: Who to whom first? How snappy? With what facial expression? Posture? The salute harbors a sub-text of its own.

Underwood personifies the self-assured military officer, expecting compliance regardless of race or rank. (His authenticity is not by chance; Underwood’s father is a retired United States Army Colonel of 28 years.) Confronted with open hostility, he holds his ground, rarely losing his cool, which is accessorized by dark aviator glasses. The two Captains’ adversarial attitude is frank and outspoken. Played without guile by O’Connell, the plainly bigoted Taylor is somehow likable.

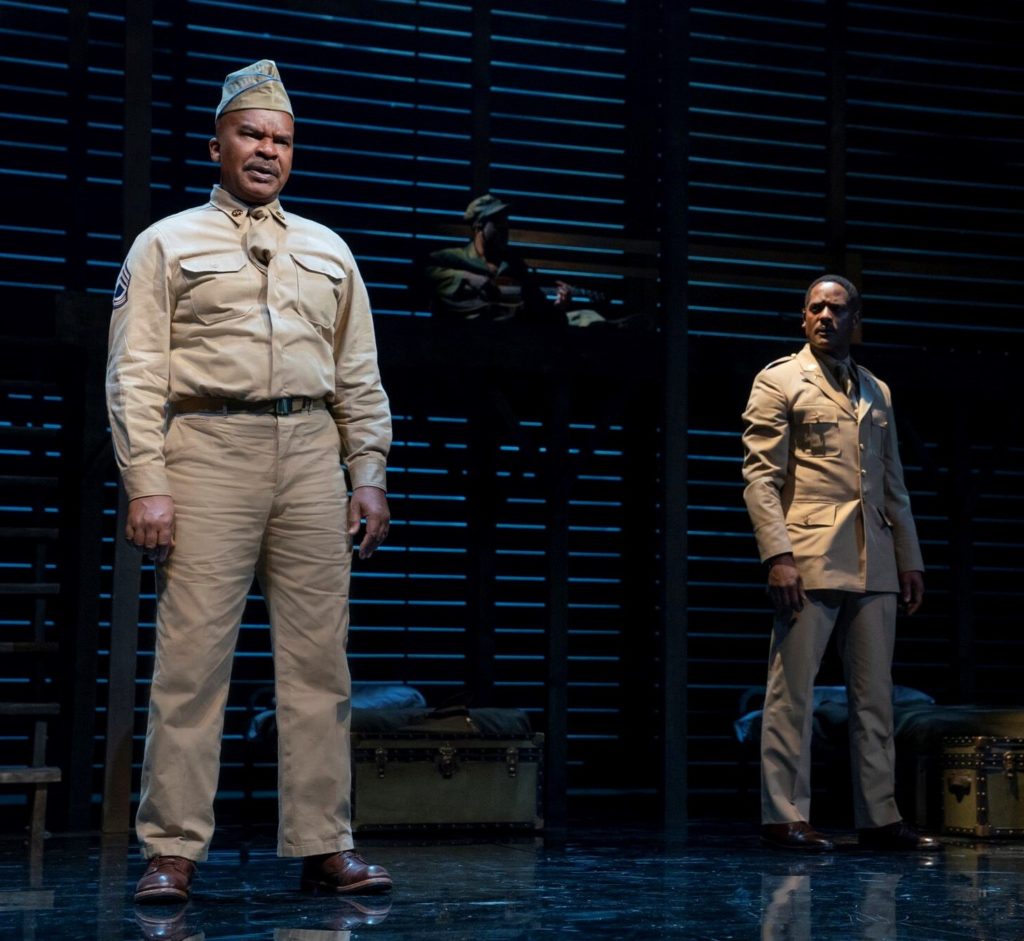

Sgt. Waters (David Alan Grier) in flashback as Capt. Davenport (Underwood) imagines from the present.

Who killed Sergeant Waters is a mystery, but who would want to kill him is not. Between targeting his most vulnerable subordinates for what he considers debasing their (and his) race, and dissing the all-white officer corps, he is universally loathed. In flashback, Waters, who is killed in a brief prologue, is a taunting menace to his men and a belligerent drunk. Scripted with Davenport observing the flashbacks from the side, Grier’s full-out nasty Waters is chilling.

It becomes increasingly clear who did not kill Waters, and therefore, who did, but director Kenny Leon’s pacing keeps the revelation from being anti-climactic. I don’t want to give anything away, but there is a line in the play that says a ton about military evolution since the play’s 1940s setting and even since the ‘80s, when it was written. “I was wrong…” Captain Taylor admits, “…about Negroes being in charge. I guess I’ll have to get used to it.” Imagine Taylor’s amazement – and Davenport’s as well – if they foresaw the eight-year period when their Commander-in-Chief would be an African-American. Or, after a reprehensible interlude, possibly a woman.

Through March 15 at American Airlines Theatre, 227 West 42nd Street, NYC. Performances Tues.-Sun. For schedule and tickets (from $59): www.roundabouttheatrecompany.org

Much had changed by the time of my U. S. Army active duty two decades after the time of Fuller’s play, but not everything. The military had been integrated by order of Harry Truman (not until July, 1948), but civilian attitudes, at least surrounding Fort Knox, Kentucky and Fort Eustis, Virginia, where I served, were yet to evolve. Unwilling to enter a restaurant or bar through a door marked White Entrance, I had little use for a pass into town.