On consecutive evenings last week, I saw what are likely the longest and shortest works, in terms of running time, currently on New York stages. The long one, clocking in at well over three hours at the Hudson Theatre on West 44th Street, is the Broadway revival of Arthur Miller’s 1949 masterpiece “Death of Salesman,” with Willy Loman and family re-imagined as Black. The sixty-minute quicky, at The Public Theater on Lafayette Street, is “Baldwin & Buckley at Cambridge,” a verbatim re-creation of the February 18, 1965 debate between writer and civil rights activist James Baldwin and conservative commentator and editor of National Review William F. Buckley, Jr., at The Cambridge Union Debate Society (in Great Britain, not Massachusetts).

Despite their divergent venues and lengths (and budgets), the two plays are uncannily aligned. “Salesman” centers on the tragic failure of a “common man” (Miller’s term), knocked about by unrealistic ideals, to achieve the mythical American Dream. The very name Willy Loman has entered the lexicon as representative of a capitalistic beatdown; presenting him as African American, especially with white-identifying opposing forces, adds a significant subplot, perhaps even relegating the play itself to that status.

What binds the two plays is the actual motion that Baldwin and Buckley argued: “Is the American Dream at the Expense of the American Negro?” Had the debate and this “Salesman” been contemporaneous, either could have drawn on the other – for reference at least, if not inspiration.

The widely acclaimed “Salesman” revival is not just a respectfully directed and acted do-over, like the Mike Nichols/Philip Seymour Hoffman 2012 production; this one is a fresh makeover. Simply (or not so) altering the Loman family to Black lends new depth to its personal and economic dynamics. That this is accomplished with only a few minor adjustments to the 1949 text (changing standout athlete Biff’s target school from then-segregated Virginia to UCLA is one), is a testament to Miller’s prescience; “Death of a Salesman” was and remains a timely commentary.

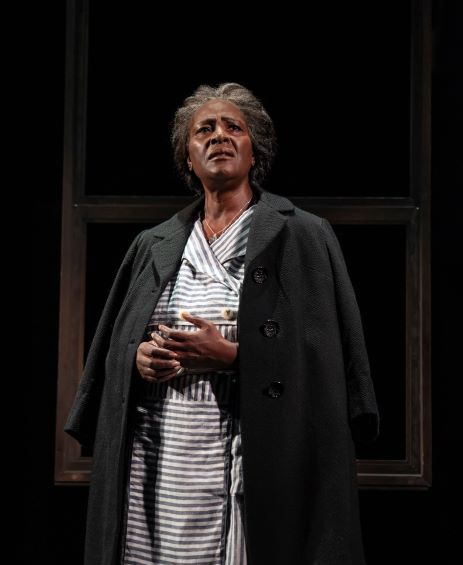

This unflattering examination of American socioeconomics originated in London in 2019, winning the Olivier Award for Best Revival as well as major acting awards for Wendell Pierce and Sharon D. Clarke, both now on Broadway. Pierce’s Willy, fatigued enough at the start (His “Oh boy, oh boy” entrance line is inexplicably omitted), deteriorates with apparent onset of dementia. Unable to acknowledge his son Biff’s shortcomings, and haunted by flashbacks to lost opportunities, themselves largely imagined, Willy loses touch with reality.

Along the way, this Willy is subject to racially coded indignities and micro-aggressions, none more devastating than those of his boss Howard, whose scripted reference to his household maid becomes a biting comment. An unscripted bit of business with Howard dropping his cigarette lighter is also wrenching. In the scene where Biff intercepts his father in Boston, another directorial gem has Willy’s pointedly white dalliance handing Biff the stockings Willy gifted her (rather than bringing home for Linda) to hold while she puts on her dress. Insult to injury.

Ms. Clarke is a formidable Linda. Not the put-upon, long-suffering helpmate of some past productions, this Linda is a strong, smart, decisive personality. She is still up against unbeatable odds, but in a more enlightened era she would represent and succeed at, if not a matriarchal household, an equal-footing one. Clarke and West End/Broadway director Miranda Cromwell nail this interpretation.

——–

James Baldwin won the 1965 debate by a 544 to 164 vote among the Cambridge Society audience. More than just hindering their own progress, Baldwin argued, the “inequalities suffered by the American Negro population of the United States” have limited access to American-dream across the board. He called out white supremacy and lamented that “the flag to which you have pledged allegiance…has not pledged allegiance to you.” Growing up, he says, it comes as a shock to discover that “while you were rooting for Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, the Indians were you!”

These and other points were firmly and convincingly presented by the charismatic Baldwin, but in performance by Greig Sargeant, who conceived the project with innovative production unit Elevator Repair Service, they flatten out: more essay than debate argument. Baldwin was rarely animated, but Sargeant, who actually resembles Baldwin, plays him excessively grim; rarely even smiling, he does not move from his position behind a lectern. Baldwin’s argument reads better than it is played.

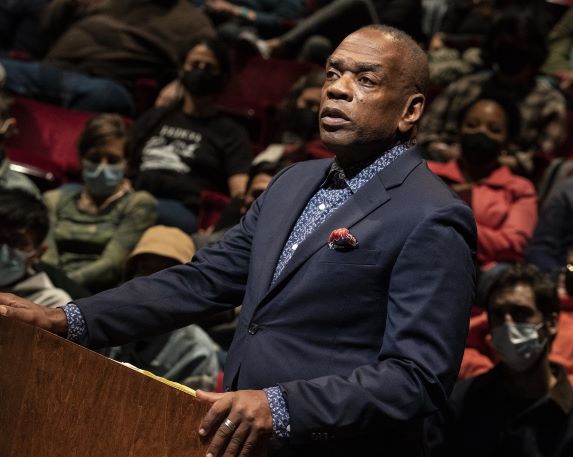

The opposite is true of his opponent’s response. Ben Jalosa Williams brings Buckley to life on the stage. Known for his prodigious intelligence, his sarcasm and rapier wit, Buckley comes off the bench swinging: Baldwin’s most striking indictment of America, Buckley begins, is the “refusal of the American community to treat him other than as a Negro.” He goes on to ‘entertain’ with disingenuous statistics (35 millionaires among the Negro community), and invokes Plato, Aristotle, St. Paul, even Jesus to bolster his defense of a system still repressive after nearly sixty years. Williams moves about, smiling (wickedly, but still…) and pointing up the occasional dry humor. At one point – only one – the actor does a spot-on imitation of Buckley’s singular vocal style of dropping his timbre to a deep baritone trail-off. Mr. Baldwin won the 1965 Cambridge Society vote, but despite agreeing with most of his argument, and disagreeing with his opponent’s reproach, I would deem Williams’s Buckley the 2022 Public Theater winner.

Whatever anyone thinks of either play, however, the disheartening takeaway is not just that the debate continues, but that it has deepened into open acrimony over the years. With no end in sight.

“Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman” continues through January 15 at the Hudson Theatre. For Tues-Sun performance schedule and tickets: www.thehudsonbroadway.com

“Baldwin and Buckley at Cambridge”’s limited run at The Public on Lafayette Street ends on Sunday, October 23.