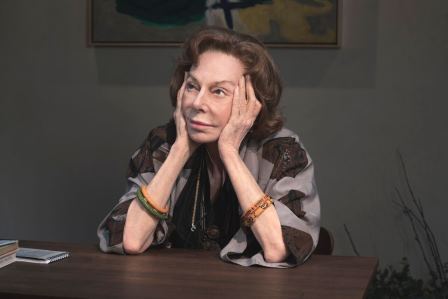

It is generally true that the decline into dementia is a gradual process. From early symptoms – forgetting names or dates or where one left the keys – to a failure to connect with the real world, can take years. In Kenneth Lonergan’s “The Waverly Gallery,” now on Broadway 18 years after its off-Broadway premiere, Elaine May enacts such a decline in just over two hours. It is an outstanding performance, mining the situation for its humor (without ridicule) and pathos (without bathos).

Heading a superlative cast that includes Tony Award-winners Joan Allen (for “Burn This”) and David Cromer (for directing “The Band’s Visit”), plus multi-film star Lucas Hedges in his Broadway debut and Lonergan-regular Michael Cera, Ms. May’s portrayal is astonishingly authentic.

Eighty-something Gladys Green has operated the Waverly Gallery in Greenwich Village for many years, exhibiting lesser-known artists’ lesser-selling works. She lives in a nearby brownstone apartment next to her grandson Daniel’s (Hedges) on the same floor. He keeps tabs on her (and gently narrates portions of the play), but as Gladys slips into forgetfulness, the burden of care falls to her daughter Ellen (Allen), and Ellen’s forbearing husband Howard (Cromer).

Gladys takes in unassuming Massachusetts artist Don (Cera), exhibiting his (charitably) ordinary paintings and allowing him to camp out in the gallery’s back room. The gallery-landlord’s decision to replace the space with a restaurant disrupts the last vestige of Gladys’s independence, leaving everyone in limbo: how and where will Gladys spend her days? And under whose supervision and care?

As Gladys declines into what we now recognize as full-blown Alzheimer’s, the degree of strain on the family keeps pace. (For his part, Don, disillusioned with the Big City, packs up his paintings, unsold save a mercy purchase by Ellen and Howard, and goes home.)

The play centers around Gladys, of course, but under Lila Neugebauer’s inclusive direction, each character, flawed as they might be (who isn’t?) is as sympathetic as the afflicted woman.

With the prospect of institutionalization dismissed, there were and still are precious few alternatives to a grin-and-bear-it approach. Move grandma/mom into the spare room and wait it out. Lonergan does not shy away from the toll exacted by the insidious disease upon its victims, including, as “The Waverly Gallery” makes clear, care-giving families.

Viewed through the prism of today’s evolving standards and awareness, the attitudes and behaviors of Gladys’s family might seem out of touch. But while 1989 is not ancient history, it is long enough ago that there was less knowledge of and support for dementia-afflicted people or their caregivers. Despite increased awareness and resources, how much has really improved is an open question. That Lonergan’s play elucidates the effects of dementia is as much a service as a literary achievement. That Elaine May enacts an afflicted woman so heart-rendingly is a theatrical miracle.

Through January 27 at Golden Theatre, 252 West 45th Street, NYC. For performance schedule and tickets ($48-$149): 800-447-7400 or online at www.telecharge.com

[I saw the off-Broadway production in March 2000. Esteemed character-actress Eileen Heckart performed the role of Gladys six times a week, with Scotty Bloch covering Wednesday and Saturday matinees. In failing health during the run, Ms. Heckart died soon after, on December 31, 2001 at age 82. Elaine May, at 86, is playing eight-a-week. That too may say something about the interval between productions. Ms. May does have an understudy, of course: Maureen Anderman, who played daughter Ellen in the original.]