Leaving the theater after a press performance of Porgy and Bess, I was asked what I thought. “I liked it a lot,” I said, “but it did drag in a few spots.” “So what?” my friend replied, and he was right.

Be it a musical play or an opera, now revised or revived, The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, its official new title, is a stunning piece of musical theater. The magnificent overture, played by a 24-piece orchestra (huge by today’s Broadway standards), segues into the hauntingly languid “Summertime,” and you know you’re in for a marvelous musical experience. And that’s even before Bess shows up, in the person of Audra McDonald.

There may be a better singer somewhere than McDonald…somewhere. And a better actress…maybe. But there’s no better combo singer/actress working in theatre today. With Norm Lewis’s Porgy, the duets “Bess, You Is My Woman Now” and “I Loves You, Porgy” (mostly hers) are as stirring to the heart as to the ear.

McDonald acts Bess’s addictions to her violent lover Crown (Phillip Boykin, really nasty) and the drug-dealing Sporting Live (a serpentine David Alan Grier) with wrenching intensity. Those addictions go into remission for a time, but the unlikely love between Bess and the deformed (although not legless as in the original) Porgy is doomed from the start.

Even with some adjustments that caused pre-opening criticism, most notably by Stephen Sondheim, the story resonates under the direction of Diane Paulus (2009 Tony-winning Hair), and the songs, arias really, soar as they might have when the piece premiered 75 years ago. “I Got Plenty of Nothing,” “A Woman Is a Sometime Thing” and “It Ain’t Necessarily So” are among the melodies that stay in your head long after the curtain comes down. So The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess drags in a few spots…so what?

Richard Rodgers Theatre, 226 West 46th Street, NYC. For schedule and tickets: Ticketmaster.com / 877-250-2929.

Mike Nichols’s meticulously directed Death of a Salesman is more faithful to the 1949 original than have been other revivals of Arthur Miller’s masterpiece. Besides replicating Jo Mielziner’s iconic set design and Alex North’s haunting background music, Nichols has guided a flawless cast in what must be as revelatory a production as was the original, reaffirming for me that Salesman is the finest American play ever written.

Salesman is not dated. Willy Loman’s situation, his inability to cope with crushing reality, might be today’s headlines, after all. And Willy and Biff Loman are universal characters; their conflict will resonate as long as there are fathers and sons.

Salesman is a tragedy, grounded in the everyday. In his preface to the play, Miller wrote: “I believe that the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were.” Willy Loman proves Miller’s point, and in playing him, Philip Seymour Hoffman drives it home.

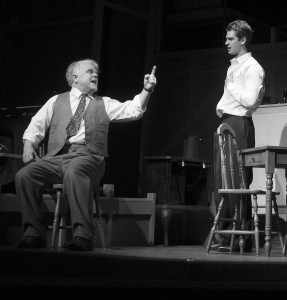

Hoffman is 44; Willy in his 60s. From the moment he shuffles onto the stage lugging the salesman’s sample cases, flops down on a kitchen chair and utters that revealing opening line “Oh, boy, oh, boy,” there is no doubt that this Willy is 60. (The original Willy, Lee J. Cobb, was only 38.)

Hoffman negotiates the labyrinth of Willy’s mind with deceptive ease. Exhaustion in the merciless present leads to confusion and fits of anger; buoyancy in the flashed-back past brings on false bravado. There’s constant turmoil in Willy’s wracked brain, spewed out in what is surely Hoffman’s finest performance to date.

Linda Emond’s Linda Loman is the very soul of helpless devotion, knowing what to do and the inability to do it. Also outstanding are Finn Wittrock as self-involved and deluded younger son Happy; Bill Camp as tolerant neighbor and rejected benefactor Charlie; John Glover as the spectral Uncle Ben; and Molly Price, who plays The Woman as just who and what she is.

Death of a Salesman is Willy and Biff’s play, and Andrew Garfield’s tormented Biff matches Hoffman’s Willy in sensitivity and intensity. Their scenes together are rich with sub-text and, in the end, explosive.

Arthur Miller sub-titled Salesman “Certain Private Conversation in Two Acts and a Requiem.” Here, the play’s private conversations speak volumes. Go eavesdrop.

Barrymore Theatre, 243 West 47th, NYC. 212-239-6200 and at Telecharge.com

I have reviewed three other “Salesman” productions: in 1984, for the Asbury Park Press, the Broadway revival with Dustin Hoffman as Willy Loman; for the Two River Times in Red Bank, Ralph Waite at Paper Mill Playhouse in 1998 and Brian Dennehy on Broadway in ’99. I played Charlie in college, and professionally, was Biff at the Asbury (Park) Playhouse in 1966 opposite Vincent Gardenia as Willy.